There were several burial cloths of Christ that were found in the tomb; and among them: the Shroud of Turin, the Cloth of Oviedo, and the precious byssus veil that was believed to cover the Face of Christ in the tomb – known as “Il Volto Santo” – The Holy Face of Manoppello. Possibly the very reason that St. John “Saw and believed.”

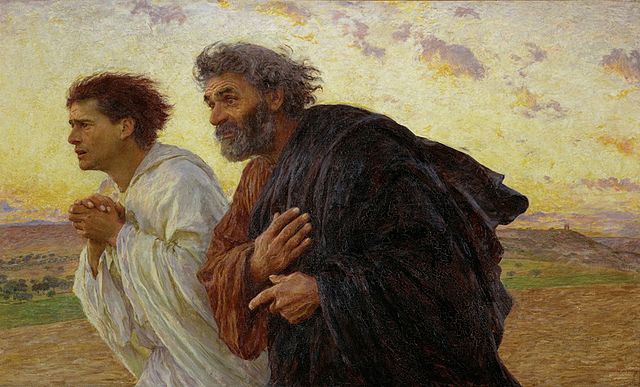

So Peter and the other disciple went out and came to the tomb.

They both ran, but the other disciple ran faster than Peter

and arrived at the tomb first;

he bent down and saw the burial cloths there, but did not go in.

When Simon Peter arrived after him,

he went into the tomb and saw the burial cloths there,

and the cloth that had covered his head,

not with the burial cloths but rolled up in a separate place.

Then the other disciple also went in,

the one who had arrived at the tomb first,

and he saw and believed.

For they did not yet understand the Scripture that he had to rise from the dead. (John 20: 1-9)

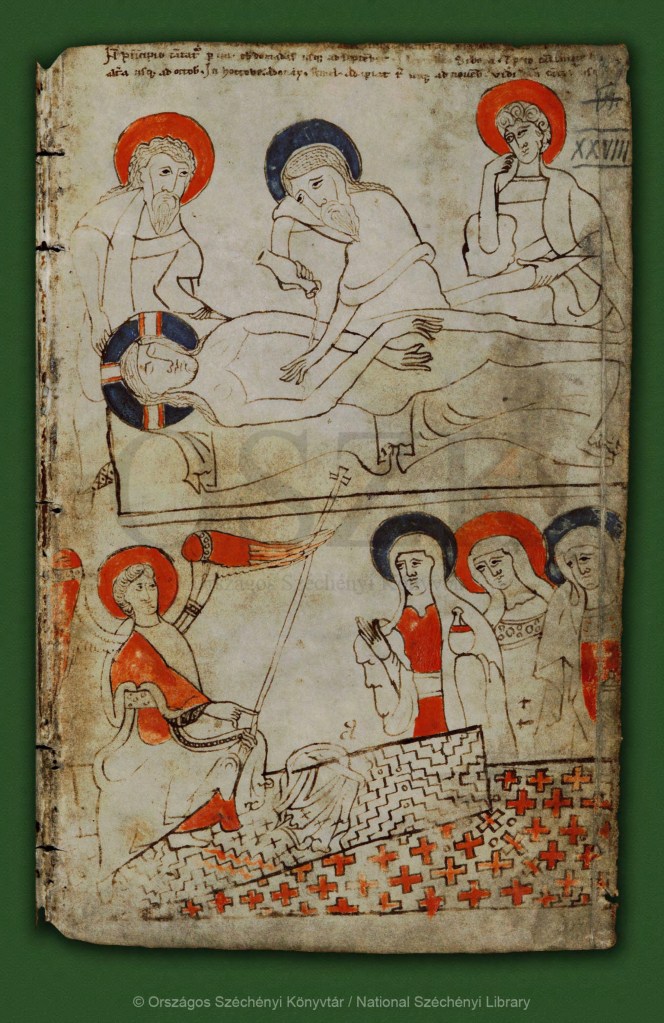

At the time of Jesus, the Jewish law required several “cloths” to be used for burial, and as many as six for someone who had died a violent death. Christian tradition has preserved six cloths as relics that are associated with the burial of Jesus – 1.) The Shroud of Turin, Italy 2.) the Sudarium of Oviedo in Spain, 3.) The Sudarium Veil of Manoppello, Italy 4.) The Sudarium of Kornelimunster in Germany, 5.) The Sindon Munda of Aachen, Germany, 6.) The Cap of Cahors in France.

Three of the cloths in particular stand out as extraordinary “witnesses” to the Passion, Death, and Resurrection of Jesus, and together they bear a powerful testimony to the truth of the Gospels. Each one bearing an imprint or image of the Face of Jesus. They are: The Sudarium of Oviedo, The Shroud of Turin, and the Sudarium Veil of Manoppello. The remarkable relationship between these three “cloths” leave little doubt that each came in contact with the face of the same man at the time of burial.

The Sudarium of Oviedo directly touched Jesus’s head following His Crucifixion. Blood was considered sacred to the Jews, so this cloth was used to soak up the Precious Blood of Jesus, by wrapping it around Jesus’s Head, as He was taken down from the Cross. The largest bloodstains are from the nose, other stains are from the eyes and other parts of the face. There is also an imprint on the sudarium of the hand of the person who held this cloth to Jesus’s Face to staunch the flow of blood. It takes one’s breath away to see that the bloodstains on the Sudarium of Oviedo, when overlaid with the Face on the Shroud of Turin and the Sudarium Veil of Manoppello, correspond perfectly. The blood type is AB, the same as on the Shroud of Turin.

“He went into the tomb and saw the burial cloths there.“

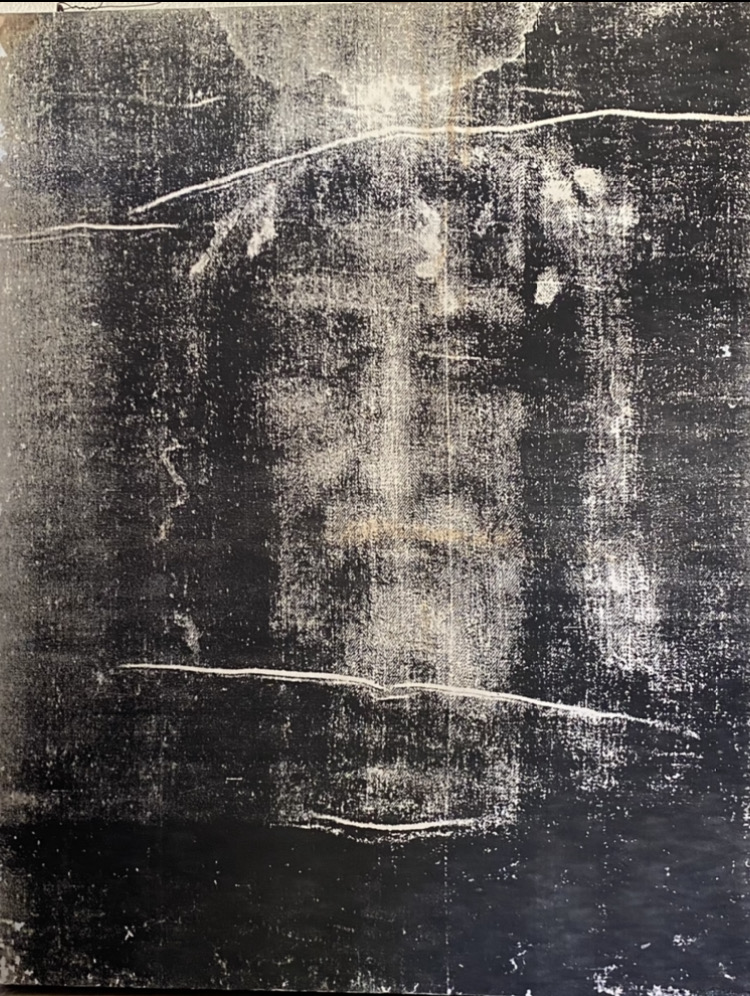

The Shroud of Turin; the sindone, or linen burial shroud, was believed to have been used to wrap the entire body of Christ. It is the most famous and studied of the three cloths. The faint but visible imprint on the Shroud of Turin gives witness to the violent torture of a man as described in the Passion and Death of Jesus in the Scripture. The world was amazed when Secondo Pia first photographed the Face on the Shroud in 1898; the negative of the photo incredibly became visible as a positive image. The Shroud of Turin caused an entire branch of science to be dedicated to its research called Sindonology.

‘…and the cloth that had covered his head,

not with the burial cloths but rolled up in a separate place.‘

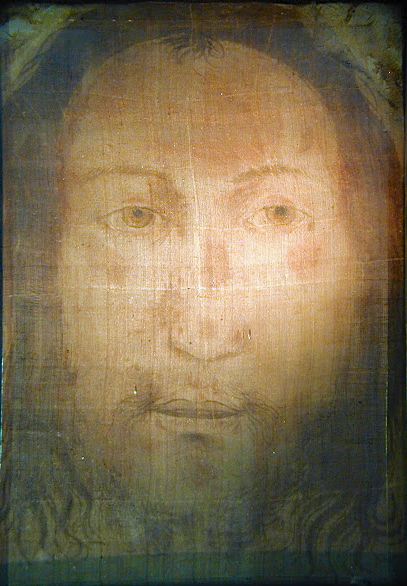

The Sudarium Veil of the Holy Face of Manoppello, Italy is perhaps the least known of the three burial “cloths.” The Veil bears the image of the living Face of Jesus. This “miracle of light,” “not made by human hands,” was protected and hidden in an isolated church in the Abbruzzi Mountains for centuries. It is believed to be the “cloth” that covered the Face of Jesus in death, showing traces of the Passion: Bruises, swelling, wounds from the Crown of Thorns, and plucked beard. But, it is also believed to have recorded in light the Face of Jesus at the moment of His Resurrection. No, this is not a contradiction. Yes, the image changes. It shows suffering, but it also shows life! It is believed to be “The cloth that covered His head.”

An explanation about the tradition of a face cloth for burial may be helpful in understanding its profound significance: In the funeral rites for priests in some Eastern churches, the veil which was used to cover the chalice and paten were placed on the face of the deceased priest. (The cloth used to cover the chalice and paten had a particular liturgical symbolism linked to the Face of Christ as well.) It was done as a symbol of both the strength and protection of God, and also of the tomb of Christ–an expression of belief in the Resurrection. In Jewish burial custom, a deceased priest’s face would be anointed with oil and then covered with a white cloth, and would have been done for Jesus.

When Pope St. John Paul II was being laid in his coffin, Archbishops Marini and Stanley Dziwisz had the honor of placing a white silk veil over the face of the pope. Poignantly, the choir sang the words from Psalm 42, “My soul thirsts for God, the living God; when will I come and see the Face of the Lord?” Many wondered about the action of covering the pope’s face with a veil because this was the first time it had been done, but was at the request of Pope John Paul II, who had dedicated the millennium to the Face of Christ.

The cloth that would cover the Face of Christ would have to be made of a material fit for a King, a High Priest, and a God. Byssus, mentioned in the Bible forty times, also known as “sea-silk,” is more rare and precious than gold and it has an exceedingly fine texture which can be woven. Made from the long tough silky filaments of Pinna Nobilis mollusks that anchor them to the seabed, it is strong enough to resist the extreme hydrodynamic forces of the sea. Byssus has a shimmering, iridescent quality which reflects light. It is extremely delicate, yet strong at the same time. It resists water, weak acids, bases, ethers, and alcohols. Byssus cannot be painted, as it does not retain pigments, it can only be dyed; and then, only purple. It can also last for more than 2000 years.

The Sudarium Veil of Manoppello is also made of rare, precious, byssus silk. The skill needed to weave a byssus veil as fine as the Veil of the Holy Face of Manoppello is exceedingly great. Chiara Vigo, known as “the last woman who weaves byssus,” has said that neither she nor anyone alive today could duplicate the gossamer-thin veil, which is sheer enough to read a newspaper through. The weave is so delicate, she says, that only the nimble fingers of a very skillful child could weave something so fine.

It is only through light that this shimmering image of the Face of Jesus may be seen, and at times appears as a “living image” as though it were reflected in a mirror, at other times the image completely disappears. Although no camera can adequately capture the image, thanks to the many amazing photos of journalist Paul Badde, the changes that occur when viewing the veil may be better appreciated. (Click here for more photos, and information about Paul Badde’s books and videos about the Holy Face.)

While the Face on the Shroud of Turin clearly shows the Face of Jesus in death with eyes closed, the Sudariam of Manoppello has eyes open–bearing witness to the Resurrection. That was the ardent belief of the former Rector of the Basilica Shrine of the Holy Face, Servant of God Padre Domenico da Cese.

There are many physiological reasons too for believing that the Face Cloth captures the first breath of the Resurrection. Sr. Blandina Paschalis Schlomer, who shares that belief, has provided meticulous research about the Veil in her book JESUS CHRIST, The Lamb and the Beautiful Shepherd, The Encounter with the Veil of Manoppello. Sr. Blandina together with Paul Badde, and Fr. Fr. Heinrich Pfeiffer, S.J., Professor at the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome, have each demonstrated that the Holy Face on the Veil of Manoppello is the proto-image of the earliest icons, and other works of art depicting the Face of Jesus.

“…and he saw and believed. For they did not yet understand the Scripture that He had to rise from the dead.”

What did St. John see in the tomb that would cause him to believe? A cloth of blood, such as the Oviedo? The Shroud of Turin? The Shroud bears a miraculous image, but it shows the Face of a dead man. A third witness was needed in order for the disciple to believe. It could only have been evidence of something as astounding as the Resurrection; proof that Jesus was alive!

It is human nature to want to see things for ourselves. Many pilgrims, humble and great, have felt called to make the journey to visit the miraculous relic. If it is God’s handiwork, and I believe that is true, then one can only wonder at its existence, and gaze in silent contemplation, giving thanks for this tremendous gift of God… so we too may “see and believe.”

“While we too seek other signs, other wonders, we do not realize that He is the real sign, God made flesh; He is the greatest miracle of the universe: all the love of God hidden in a human heart, in a human face.”

~ Pope Benedict XVI

“We cannot stop at the image of the Crucified One; He is the Risen One!”

~ Pope St. John Paul II

Alleluia! Alleluia! Alleluia!